admin

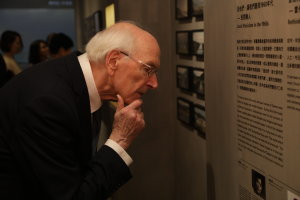

Father Alois Osterwalder, founder of the Ostasien-Institut (OAI) in Bonn (Germany), and well-known in circles of music researchers as an indefatigable organizer and promoter of Chinese musical culture, has died from heart failure at his home in Rösrath in Germany. He passed away peacefully during an afternoon nap on the 23rd of July, 2021. He was 88. Participants in CHIME meetings will perhaps remember him best for the recordings of traditional music, opera costumes and musical instruments which he arranged to be collected in Taiwan. These were kept at the Ostasien-Institut since the 1960s, were the subject of various documentary films and academic presentations, and were returned by OAI to Taiwan as a gift in 2018, to be formally exhibited and researched there.

In 2015 Osterwalder was awarded the Taiwanese-French Culture Prize by the Fondation culturelle franco-taiwanaise in Paris for his life-long services in the realm of cultural exchange between Europe and Taiwan. Osterwalder set up cultural and academic platforms, organized exhibitions and international conferences, such as ‘Europe meets China, China meets Europe’ in 2012, and in October 2014 the fine symposium ‘The Strange Sound’, devoted entirely to Chinese music, held at his institute in Bonn, events which resulted in fine book publications.

Those who have had the privilege of meeting Alois Osterwalder in person will remember him as an extraordinarily kind, sensitive and committed man, very much the person to build bridges, not just between cultures, but between individual human beings. Undoubtedly this was at the heart of everything he undertook: his curiosity towards others, and how one might bridge gaps between people from very different cultural backgrounds, and arrive at a better understanding of what moved them. His wisdom and his fine sense of humour – those who knew him will remember that special twinkle in his eye! – must have stood him in good stead in these tasks.

As he told a Swiss newspaper reporter in 2010: “I have always had China on my mind, from the time when I was a child. I also dreamt of it.”

Alois Osterwalder was born 19 February 1933 on a local farm in Engelsburg in Switzerland. Dreaming of China, and keen to become a missionary, he attended the Gymnasium of the Steyler Missionaries in Rheineck, studied theology in Mödling near Vienna, and became a priest, but also an academician. In both qualities he spent a lifetime building bridges between the West and East Asia.

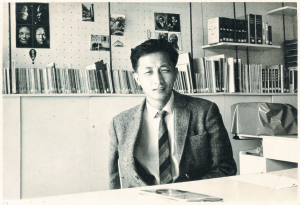

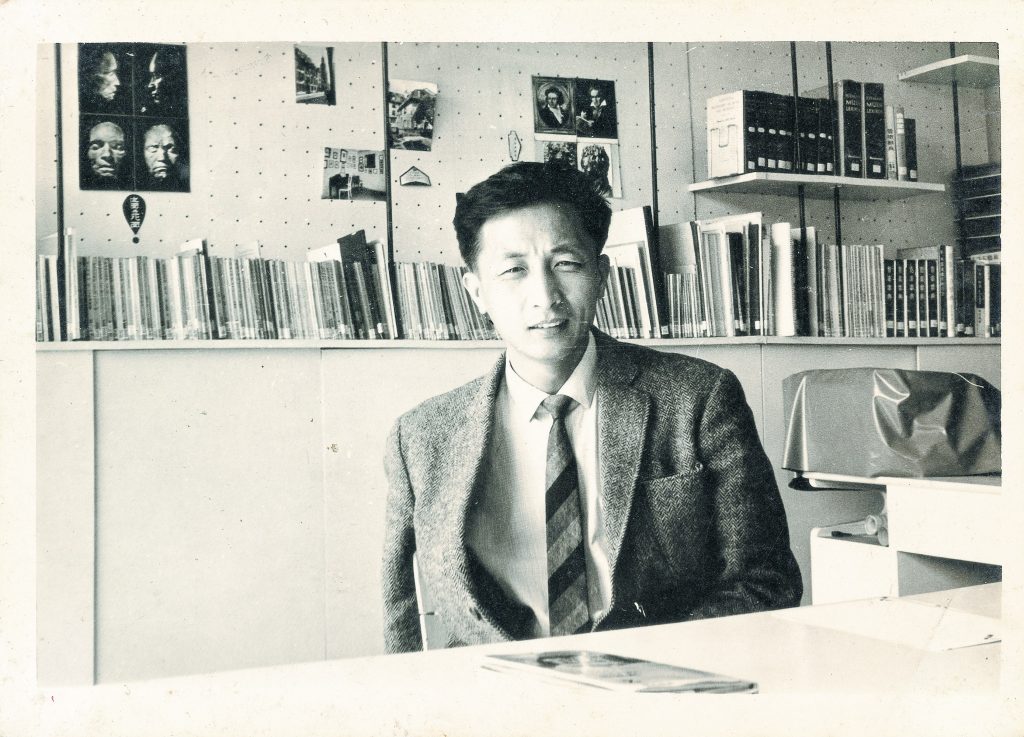

Pursuing his studies in Munich and in Bonn, he took up Sinology in 1960, at a time when China was redder than red. Osterwalder kept up his interests in Chinese culture, and also in the cultures of wider Asia, notably Japan. But China was his most important focus. He helped talented young Chinese to pursue their studies in the West, and in 1965, with like-minded friends, including the China-born musician and composer from Taiwan, Shih Wei-Liang, founded the China-Europe Association (Arbeitsgemeinschaft China-Europa), which eventually (in 1969) became the Ostasien-Institut.

Osterwalder raised funds for Shih Wei-Liang to return to Taiwan to establish Taiwan’s first musical library, and to contribute to Taiwan’s Folk Song Collecting Movement by collecting songs and theatrical music among Chinese and regional indigenous communities, including people who had migrated from Mainland China in the late 1940s. A further aim was to establish a Centre for Chinese Music Studies in Bonn. The materials which Shih Wei-Liang sent to Germany were carefully stored and preserved, and formed the basis for this Centre, and for the Institute’s Bonn Collection of Taiwan Music. Alois Osterwalder spent the final decade of his life continuing his passionate work of cultural promotion and exchange, but he suffered a heart insufficiency in 2019 and had to take things more easily. During his final years he enjoyed ample support from his partner Shu Jyuan (Claire) Deiwiks, who was closely involved in his Taiwan projects and became a treasured friend.

Alois Osterwalder has been cremated, and his ashes will be strewn out at the root of a Gingko tree – perhaps in a fitting tribute to the continued meaningfulness of a life that was filled with good aspirations, and may serve as a model for many of us.

Frank Kouwenhoven, CHIME

Klänge aus Ostasien: a memorable concert of new Taiwanese music held in Bonn

Von Frank Kouwenhoven, CHIME. Auch veröffentlicht auf https://www.zo.uni-heidelberg.de/sinologie/shan/nl-archiv/2022_NL113_4.html.

On 2 October 2022 the Chamber Music Hall of the Beethoven House in Bonn offered a unique opportunity to get acquainted with new music from Taiwan. An ad hoc ensemble of eleven musicians, handpicked by Berlin-based conductor Yu-An Chang, played seven pieces by young upcoming talents and established composers from Taiwan.

The attractive programme included three world premieres and also some showcase pieces highlighting traditional Chinese instruments.

There was a lot to ‘dig into’ for Western ears. The new pieces were complex and demanding, a challenge for performers and listeners alike, but the hall (packed to the brim) responded warmly to the event, even with a sense of excitement about something unique taking place.

It must have been a tour de force to bring all these musicians from different parts of Germany, Austria and Sweden together, and rehearse with them, in the span of just three days, this fairly ambitious programme. They brought it off splendidly, making a convincing case for new music from Taiwan, a realm that merits ample attention.

It may be that the benevolent spirit of the late Alois Osterwalder hovered over this entire initiative, and helped to open people’s minds and ears. Many who came to listen had known Osterwalder in person, or were at least familiar with the (Bonn-based) East Asia Institute (OAI) which he founded in the 1960s. The concert was held as a special event in his memory.

Osterwalder, who died from ilness in July 2021, was a life-long passionate initiator in the realm of cultural exchange with East Asia. One of his many achievements was reviving a long-dormant treasure of sound recordings of rural folk music: fifty-six open reel tapes, with fascinating ritual songs and sounds from Hakka, Hoklo and aboriginal groups from Taiwan, collected by the Taiwanese music scholar Shi Wei-liang and others in the 1960s and 70s. The tapes with these songs slumbered in the OAI’s archives until Osterwalder brought them to the light again and asked present-day music scholars in Taiwan to investigate and take care of the collection. All the recordings were digitalized, and selections of them researched and published on four cds.

But Osterwalder’s idea was to do still more with them. This became the point of departure for the programme in Bonn: several composers took inspiration from the recordings, and quoted fragments of Taiwanese aboriginal song in their new works, and in some cases they were inspired to ponder, in their newly commissioned pieces, on the implications of sonic ‘preservation’ or on aspects of early sound recording technique.

It had been an explicit wish of Osterwalder that the folksongs, in addition to serving as cultural documents, would become an inspirational source for musicians and composers.

As a result, the audience in Bonn was served a surprising musical menu, including snippets of authentic Taiwanese folk song, embedded in contemporary instrumental writing, but also a range of other uncommon sounds, from whale song to evocations of Eastern landscapes and Chinese literati life! Midway during the programme, there was a bonus in the shape of a brief documentary film on Alois Osterwalder. The film portrayed him as the congenial and inspiring man he was.

The concert became a fascinating window on the current state of new Taiwanese music, as well as a fitting tribute to Osterwalder. Perhaps it was not entirely coincidental that the aboriginal song ‘sisila ila ila’ (Saying Goodbye) ran as a thread through the programme.

As a long-time scholar of Chinese folk song, and as a musicologist who has written extensively on Chinese contemporary music (though mostly in connection with Mainland China), I was curious to hear this concert and to interview some of the composers. I gladly take the opportunity to reflect a bit on the special nature and content of this event.

Some preliminary thoughts on Taiwanese/Chinese new music

In so far as most composers in Taiwan are ethnically Chinese, we can refer to their works as ‘Chinese’, bearing in mind that these artists do not think of themselves as ‘Chinese’ in any political sense: they don’t subscribe to claims on the part of the People’s Republic that Taiwan is a part of Communist China. It may not always be easy for Taiwanese composers to interact with Westerners, who often simply take them to be ‘Chinese’, forgetful of the political implications of that label. People in Taiwan generally see their native soil as autonomous, as a culture and territory in its own right, with a history and development of its own. In practical terms, the PRC government has never set foot on Taiwan, and the country operates as an independent state, ruled by a democratically elected government. This arguably puts Taiwan in a domain quite different from that of the PRC.

Naturally, history, language, and musical idioms still intimately connect the cultures on both sides of the Taiwan Strait, so I hope I may still legitimately speak of a broader shared realm of ‘new Chinese music’.

So, what were my impressions of that music during the concert in Bonn? And how did the works played by Yu-An’s ensemble affect the audience in Bonn?

Generally speaking, if Western audiences are familiar with new Chinese music, it mostly tends to be through a handful of composers from the People’s Republic: artists like Tan Dun, who began to be noticed abroad in the mid-1980s. At that time, there was a sudden upsurge of interest in new Chinese music. Pioneers from the PRC, co-including Guo Wenjing, Chen Qigang, Xu Shuya and several others, were soon praised as the new ‘Chinese Beethovens’. Of course, there’s a good deal more to the story of new Chinese music than that, also before the 1980s.

Among older generation figures, Chou Wen-chung (1923-2019), again from Mainland China, made a name in the United States as a disciple of Edgar Varèse already in the 1950s and 60s, and he became a veritable ambassador for Chinese culture once he established the Center for US-China Arts Exchange at Columbia University in 1979. Composers in Hong Kong also earned respectable reputations abroad decades before Tan Dun and his colleagues rose to fame. We should also not forget the important contributions made by prominent Taiwanese pioneers such as Pan Hwang-long (b.1945) and Ma Shui-long (1939-2015), whose works began to be performed abroad from the 1970s onwards, or Hsu Tsang-houei (1929-2001), who studied with Jolivet and Messiaen in Paris in the 1950s and upon his return to Taiwan in 1959 became an active teacher and organizer. Hsu enthusiastically introduced new music to Taiwanese audiences via numerous concerts and talks.

So how do Taiwanese composers of today compare with their counterparts in other Chinese-speaking parts of the world? To be honest, I don’t think there’s is any meaningful way to make general distinctions, at least not in terms of musical style. The concert in Bonn has not changed my view on that.

There’s no lack of strong Chinese personalities or individual histories in contemporary music, but precisely that circumstance has created a caleidoscopic and multifaceted realm of new artists and new sounds: we live in a global world today, where composers connect with many different sonic realms and cultures, and will pick their own preferred sources of inspiration and use them in whatever way they like. As Ching-wen Chao (b.1973) put it succinctly in an interview I had with her in Bonn: ‘We don’t serve style. I don’t write a piece to prove my culture. I’m not writing for any “-ism”.’

Surely there ought to be no ‘obligations’ for artists to sound ‘Chinese’ – no matter what scholars or politicians in the PRC may say on this subject. Ultimately, what ‘Chinese’ means, in any musical context, will always be subject to change. It is more than likely to be redefined and transformed with every new generation of artists that turns up. It is like that everywhere in the world. What ‘American’ music meant in the 18th and 19th centuries was a far cry from what it came to mean afterwards, due the influx of African music and the rise of genres like blues, soul, gospel, and jazz. This major shift in the USA was obviously not the result of a carefully orchestrated governmental campaign. It was a spontaneous thing, with people just responding creatively to what fascinating new sounds they heard. I doubt that any government could ever ‘organize’ anything like this to happen. You might be able to force artists to adopt some sort of standard gown (as it has happened throughout history, even to Mozart when he was forced to write church music in Salzburg), but then there will always be the potential danger of killing an artist’s joy and of badly compromising artistic values.

Having said this, many composers on both sides of the Taiwan Strait have recognized the rich potential of native Chinese traditions, and were (or still are) exploring it at length. PRC artists like Tan Dun grew up as teenagers during the Cultural Revolution, and gathered first-hand experience in the countryside, some of them working directly with rural village bands and local folk or opera singers during the 1970s. Many Taiwanese composers grew up in the vicinity of urban temples or opera theatres in Taiwan, and likewise felt inspired to incorporate musical elements from such sources, or from aboriginal songs, in their own music.

Meanwhile, there can be no denying that formal musical education, on both sides of the Strait, has been (and currently still is) overwhelmingly focused on Western models, Western methods and ideals, Western formats of ‘classical’ music: the symphony, the sonata, the piano trio, the cantata… Popular media in Mainland China and in Taiwan mainly tend to broadcast Asian and Western pop music. So given this situation, it is not surprising to see that most young people in East Asia grow up with a limited sense of native tradition, or with no sense of it at all. Is it a problem? It sure marks a cultural rift of sorts, but human history tends to be full of such rifts. Think again of American music, of the gap separating, say, the (German-romantic oriented) music of Amy Beach or Edward MacDowell from such artists as Duke Ellington, George Gershwin or Aaron Copland. Ultimately, the real vitality of any culture resides in such a rich and simultaneous occurrence of different styles and idioms , not in any rigid nationalist model for how music should sound.

So in the end, it shouldn’t matter where composers take their cues from. The valid criteria for appreciating new music can only be things like sincerity, flair, heartfelt emotions, individuality, technical craftsmanship, commitment to one’s chosen materials, and probably also some ability to surprise and to provoke. There was certainly no lack of all of that in the programme presented on 2 October in Bonn.

Chinese instruments at the Bonn event

One reason why young Asian composers might still be explicitly interested to explore Chinese traditional instruments, and write for such forces, is purely pragmatic: Asian players of native instruments are more keen to experiment and to try out new sounds than their counterparts who play a violin or piano or clarinet. Musicians of the latter group have mostly taken up Western instruments because they are especially fond of Western classical music. They have a wealth of already existing Western classical repertoire to tackle, and only few of them feel inclined to try their hand at newly composed works: with new music you never know in advance what you get, a modern score might take a long time to master, and perhaps it would attract only a limited audience. Interestingly, this attitude appears to be widespread among players of Western instruments both in Taiwan and in the PRC.

By contrast, players of Chinese instruments are more eager to try out new things and dive into new repertoire: in that way they can reach beyond the perpetual handful of evergreens they already know and play, and with which local Asian audiences already tend to be (overly) familiar. If you want to expand the techniques of a Chinese instrument and explore new horizons, turning to present-day composers would seem to the logical thing to do.

The concert in Bonn featured four fine soloists of this kind – playing Chinese plucked zither zheng, bamboo flutes (di and xiao) and two types of plucked lutes, liuqin and pipa – and all of them offering memorable contributions.

Young liuqin (small four-stringed lute) player Chia-Ling Chang (based in Freiburg) made a really formidable impression in ‘Sound Color Density’, a duo for liuqin with piano, in which she was accompanied by pianist Tomoki Park: breathtakingly virtuosic and dynamic music, which brought out the best in the two players. It was wonderful, too, as a visual experience, a bit like two young tigers dancing around each another in utmost concentration, performing with hair-raising precision the fast chromatic runs, going to and fro with their gestures, and the piano part was sometimes reminiscent of Stockhausen. Powerful stuff.

The piece was written by Chihchun Chi-sun Lee (b.1970), it was first heard in 2012 in Taipei (with different musicians), and now it received its Bonn premiere with the present two players. Lee is a prolific composer, successful both in the United States, Europe and at home, in Taiwan, with major prizes and awards to her name. She refers to herself as a Taiwanese-American composer but currently resides in South Korea. The title of her work referred to the three short movements of which it consisted, each movement emphasizing a different aspect of the interplay between liuqin and piano; the first one focused on texture, the second one explored timbre (and silence), and the third one constituted a synthesis and finale.

The combination of liuqin and piano is not exactly very common. I often find attempts to combine Chinese instruments with piano a bad idea, since there’s the danger of the rich overtone spectrum of the keyboard drowning out the more typical timbral qualities of Chinese strings or pipes, and there may also occur intonation problems. Luckily, nothing of this kind occurred in this piece. Lee knew what she was doing, and created a convincing, lively dialogue, giving each of the two players their full due. The many unusual plucking and stroking techniques on the liuqin were a feast both for the ear and for the eye.

The other traditional Chinese solo contribution happened to be of a very different kind: Fan-Qi Wu, a young Taiwanese pipa player currently based in Sweden, presented one of the eternal evergreen pieces of the classical pipa repertoire, the mellifluous Yue Er Gao (‘Moon on high’). Squeezed in between two contemporary works, this piece immediately made one realize how far the two worlds (modern composition and Chinese classical tradition) are mutually removed, not just in sound, but also in structure: Yue Er Gao is essentially a suite, a string of tunes; one might impolitely describe it as ‘one damn thing after another’. In Western and in modern composition, themes and motifs are more often developed, artfully blended and then gradually transformed, but it would be meaningless to try and understand traditional Chinese pieces on such terms. Fan-Qi Wu lovingly realized the late 18th century Yue Er Gao, in all its subtle turns of phrase and delicate transitions. It was a nice idea to insert such a piece, which must have counted as ‘new music’, too, for most of the Western listeners present. And of course, like the other traditional-Chinese instrument players, Wu was mobilized also in the contemporary works on the programme, where very different playing techniques were required.

The other players of Chinese instruments in the concert – Ming Wang on zheng (bridged zither) and Yi-Hsing Chiu on bamboo flute – were not given special solos, but their contributions in the ensemble were impeccable. Same goes for the Asian musicians in the group who played Western instruments: clarinetist Yung-Ping Deng could only be heard in the final piece, while Soyeon Park (on double bass) and Min-Tzu Lee (percussion) featured in several pieces.

Whale songs and music of farewell

The concert started and ended with a tour de force for Japanese viola player Megumi Kasakawa.

Kasakawa was initially educated as an instrumentalist in Osaka in Japan and at the Music Conservatory in Geneva, before moving to Germany, where she joined the Ensemble Modern (Frankfurt am Main) in 2010. She is still active in EM today. She was given a lot to do in Bonnt, not only two special solo works, but also several contributions as an ensemble player in other pieces.

The opening work in the programme, ‘sisila ila ila’ – ‘Saying Goodbye’, was a dialogue between viola and a SaiSiyat ethnic minority song, of which snippets of a field recording were played. Written especially for the Bonn concert, the work gave full reign to the full-bodied, beautifully poised tone of Kasakawa’s viola, without drifting towards empty spectacle: this was not a show piece, but a work of quiet contemplation. The score required a modest vocal contribution from Kasakawa: at one point she took over the folk singer’s ground tone with her own voice.

When American-based Taiwanese composer Shih-hui Chen (b.1962) began to prepare for the writing of this piece, and turned to the recordings of aboriginal songs, she realized that the collecting of such materials in Taiwan in the 1960s coincided with a very different act of preservation: in 1966, whales in the waters around Taiwan became a formally protected species. Together with sharks, manta rays and other ocean creatures, they are now formally included in Taiwan’s Wildlife Conservation Act. In ‘sisila ila ila’, Chen wanted to celebrate this double effort at conservation, and to honour the attitude of showing genuine care for both culture and nature: she incorporated an authentic folk song recording, and picked the viola because of its perceived closeness to the human voice. She made Kasekawa’s viola embroider on melodic motives from the folk song, but also imitate snippets of whale song, e.g. in several high-pitched rapid upward string glissandi.

For Chen, who lives in the United States since 1982 and teaches music at Rice University in Texas, this was hardly the first work to be inspired by native traditions. Cooperating with the Institute of Ethnology of the Academia Sinica, she carried out two years of musicological study on indigenous Taiwanese songs and on nanyin (a genre of refined love ballads in Minnan dialect), already resulting in various orchestral and electronic works prior to the piece we heard in Bonn.

The sounds of the folk singer in ‘sisila ila ila’ were mostly allowed to stand on their own, even if frequently heard simultaneously with the viola, because the timbres of the two ‘voices’ were kept apart as distinct sonic realms in Chen’s score. Not so much a ‘dialogue’, but a spontaneous and attractive confluence of sounds. The result was an original and intriguing piece, one that the composer is currently thinking of expanding into a longer (perhaps 70-minute) composition with added theatrical elements. Chen is quite active as a composer for the theatre; she recently also finished an opera which, she feels, addresses the same fundamental question as the work heard in Bonn: ‘How do we define ourselves as humans in society?’ How can we meaningfully position ourselves in a wider (cultural and natural) environment?

The same question probably also loomed at the heart of the work heard at the very end of the concert, Ching-Wen Chao’s Dark Light (2016), again with a solo part for the viola. But more about that in a minute.

Recorded sounds of Taiwanese folk song also featured in the second commissioned piece in the concert, Ling-Hsuan Huang’s ‘etching’, for a mixed ensemble of Chinese and Western instruments. Here the aim was clearly no celebration of preserved folk music. Ling-Hsuan Huang (b.1991), who studied composition in Taipei, Berlin and Karlsruhe, as well as sonology at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague, developed a special interest in (as she calls it) ‘the study of artificial resonance in acoustic and ritual elements’. What that meant became evident in ‘Etching’. The title refers to the earliest available sound technique, that of Edison’s Phonograph, a machine which (with its characteristic big horn) was widely used as a device to collect folk songs in the early 1900s. Such aficionados as Percy Grainger, Constantin Brailoiu, Béla Bartòk, Cecil Sharp and many others all dragged it along on their excursions. The sounds sung or played into the horn would be etched with a needle directly onto a wax cylinder.

The tape recordings of Taiwanese songs from the 1960s obviously employ very different techniques of sound registration, but (like the wax cylinders) they still yield a notable amount of hiss. Such mechanical noise is normally unwanted, but Huang was fascinated precisely by these extra sounds. She made it her point of departure in ‘etching’, in which she employed an ensemble of nine players plus two ‘primitive’ cassette tape recorders. Snippets of recordings were played on those machines by pressing the ‘play’ button. This time, the folk singer’s voice mostly stayed in the background, while such mechanical noises as ticking, cracking, and hissing were given pride of place, happily imitated and amplified by the instrumental ensemble. This seemed to take on ritual dimensions by the time the string players picked up ribbons of cassette tape and started to rub them against their strings (most clearly audible on the zheng zither), as if they were ‘recording machines’. It was funny and weird to watch and to hear, the music perhaps struck me a bit like a poem that one fails to grasp in semantic terms,while still finding it effective for its mystery and amusing in its sonic appeal. The piece ended, appropriately, with the pipa player pressing the ‘stop’ button and all music coming to an abrupt standstill. I’d be curious to hear more of Huang’s works, but this would actually be true for all the composers featuring in this concert.

The third commissioned work, Lily Chen’s ‘Sprawling like vines’ (Bieli mansheng) once again took up the ‘sisila ila ila’ song as a source of material, this time without directly using a sound recording. Lily Chen (b.1985) studied composition in Taipei and at UCLA in California. In ‘Sprawling like vines’ she uses the microtonal intervals and the parallel singing of the SaySiyat to help provide structure in her delicate ensemble piece. Fragments from the folk tune are intertwined to evoke an atmosphere of (I assume) two people entangled in some emotional kind of farewell. No lack of Abschied in this programme!

Lily Chen’s work was easily the most fragile piece in the concert, opening with very high-pitched sounds on dizi (bamboo flute) and violin, and featuring some really fine and delicate timbral effects. Compared to the other works, I found it harder to detect a sense of direction in this work, for which a single hearing apparently did not suffice.

By contrast, the one before last work in the programme, a piano trio titled ‘Formosa Trio’ by Tyzen Hsiao (1938-2015), came as a real surprise: it turned out to be a completely tonal romantic work, the oldest piece in the programme (written 1996), with faint echoes of Chausson and Debussy, and of several one-movement ‘phantasy trios’ written by English composers in the early part of the 20th century. So, was this music too ‘old-fashioned’, too ‘retro’, compared to the rest? Luckily, there is no ‘ban’ on tonal music any more on present-day contemporary music stages. I suspect the audience in Bonn actually welcomed this piece, finding it a soothing diversion after the preceding ‘austere’ contemporary works.

Hsiao, a Taiwanese-American composer born in Kaohsiung, initially studied music in Japan, and he ultimately settled in the USA in 1977. He took inspiration primarily from Western classical idioms and church music, but the titles of his prolific oeuvre of vocal, chamber and orchestral works also made ample reference to native themes, native scenery etc. There was nothing recognizably ‘Taiwanese’ for me in the ‘Formosa Trio’ (Formosa being an older name for Taiwan), but it was a tightly organized, well-argued work, full of appealing lyricism, and gorgeously performed by Korean violinist Yezu Elizabeth Woo, pianist Tomoki Park and cellist WenTeng Chang. The latter (from Taiwan, now based in Berlin) is still studying cello, while the other two performers already embarked on busy concert careers. Woo is definitely a name to remember. She first came to attention when, as a sixteen-year old, she played all of Paganini’s 24 Capricci for solo violin at Carnegie Hall. She made the violin sing and soar in the trio, and Park was no less of a virtuoso on the keyboard. What I liked quite generally about this concert was that individual differences in levels of accomplishment seemed to blotted out: all the eleven players in the ensemble, whether advanced professionals or upcoming talents, were giving their very best, and managed to form a perfect unit in the ensemble pieces. In the trio, such perfect unity was achieved without the players ever sounding slick or routine-like. That is the real balancing act, I guess: always to study your head off until you can play all the notes to perfection, but then, in performance, to sound as if you are hearing it all for the very first time! Only the best can retain such a sense of wonderment.

In that respect, the final work on the programme, Ching-Wen Chao’s ‘Dark Light’ (2016) must have felt like a special challenge, a piece de résistance. It brought all the musicians together, and it needed more rehearsal than the other works, in order to overcome problems of balance, not just between Chinese bamboo flute and Western clarinet (a tricky combination), but also more generally between the forces employed. Amongst other things, the score required a formidable battery of percussion, and also some vocal contributions from the performers, ranging from sighing to hissing.

‘Dark Light’, for solo viola and ensemble, was originally written for the Dutch Nieuw Ensemble, and premiered by violist Frank Brakkee and his colleagues in Amsterdam in 2016. The piece had to be partly rescored for Bonn to involve the Chinese instruments, and so it basically became yet another ‘premiere’ piece.

There was some tension among the musicians the first time they tackled this work in rehearsal; it was clearly not an easy score to deal with, but it all worked out fine in the end.

Ching-Wen Chao (b.1973) is yet another Taiwanese composer who, after studying composition in Taipei, continued her musical training in the United States, in her case at Stanford University with Brian Ferneyhough, Chris Chafe, and notably Jonathan Harvey, whom she honours as a great mentor. She also spent time in Germany, participating in courses for new music in Darmstadt and later with Stockhausen in Kürten. Her works were performed at many prominent festivals around the globe, she taught for years at Stanford University, and later became a cultural organizer and professor of music in Taipei, stationed at National Taiwan Normal University.

‘Dark Light’ was inspired by the thousand-year old qin (classical seven-stringed zither) piece Fan Cang Lang (‘Rowing in a Vast Billowing River’). The composer did not so much take any musical cues from this qin piece, but instead embroidered on the story behind its title, which also (in the past) inspired a number of famous traditional Chinese landscape ink paintings.

So what is the story? In medieval China lived many famous poets and other artists who, at some time, occupied important positions at the Chinese court. Sometimes they would directly advise the emperor about affairs of state. That was, of course, a tricky business, and quite a few of these intellectuals, perhaps too outspoken and frank, would eventually fall from grace and end up in exile: they’d be sent away to remote parts of the country, to whither away as they pleased. Exile even became a kind of proud emblem for many of the banned scholar-poets. And they sure did not waste their time, but continued to write poems, eulogizing the grand and wild scenery around them, and leading their solitary lives. It was all very lofty and spirited, but perhaps some of these people secretly longed back to their former power and influence at the court… The eternal push and pull between the spiritual and the world of earthly human strife may even lie at the heart of the qin-piece Fan Cang Lang: it presumably depicts an exiled scholar, rowing a boat near the conunction of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers. Amid clouds and mist, and traveling on waves that are sometimes calm, at times whipped up by storm or by rapid currents, the scholar pesumably responds to this constantly changing environment: he may feels in turns calm and upset, and the landscape become a metaphor, evoking in turns the lofty realm of spirituality and the world of human strife and imperfection.

This contrast also comes to the fore in Chao’s ‘Dark Light’, where rapidly shifting pentatonic clusters serve to invoke ‘colour’ in what would otherwise have remained just a grey Chinese brush painting. The solo viola portrays the river, flowing calmly or getting wild in turns. An important part of the ‘colouring’ is also done by the percussion, which was skilfully operated by Min-Tzu Lee.. Like the viola player, she had a fairly busy evening, with frequent re-arrangements of percussion instruments, and with some fairly demanding parts, certainly in ‘Dark Light’. I found her contributions to that work every bit as engaging as the arabesques of the solo viola played by Megumi Kasakawa. Everything in the piece was expertly held together by Yu-An Chang, a no-nonsense conductor with a sharp ear, and a real heart for the music performed in this concert.

Behind the scenes, his wife Kai-Chuan Tang had a busy time dealing with logistics, making sure that the frequent re-arrangements on-stage would be carried out smoothly. Mariana Münning and Josie-Marie Perkuhn acted as sympathetic moderators, and Claire Shu-Jyuan Deiwiks, one of the driving forces at the OAI in Bonn, and a life companion to Alois Osterwalder, was one of the main spirits to get this concert off the ground in the first place. She gave a short moving speech at the start of the evening, in which she lauded the participants, and also thanked the Cultural Ministry of Taiwan for its generous support.

I hope this concert won’t remain an isolated event. In Europe, we are keen to meet more musicians and hear more new music from that particularly corner of the globe! Certainly now that Mainland China appears to be isolating itself with too rigid anti-corona policies (to the detriment of its economy and culture), we depend on Taiwan to open up more corridors to the world, and to take the honneurs. As Ching-Wen Chao told me during our interview, musical life in Taiwan is currently quite rich and diverse, with ample investments in theatre events, visual arts, movies, opera etc. The special ‘vibes’ and excitement of all that activity certainly seemed to echo in the wonderful vigour of this concert in Bonn. More of that, please!

Frank Kouwenhoven

CHIME Foundation, The Netherlands

Anlässlich des Konzerts KLÄNGE AUS OSTASIEN am 2.10.2022 erscheinen zwei chinesischsprachige Artikel in der taiwanischen Presse:

„Liebe über große Distanz – Alois Osterwalder, Bewahrer der Aufnahmen des Folk Song Collection Movements“ mit vielen Bildern: https://www.cna.com.tw/culture/article/20220912w001

und

„Konzert im Beethoven-Haus: Wir erinnern an den Helfer hinter den Kulissen des Folk Song Collection Movements“: https://www.cna.com.tw/news/acul/202208070209.aspx

Chang Yu-An, der Dirigent des Konzerts KLÄNGE AUS OSTASIEN am 2. Oktober 2022 im Kammermusiksaal des Beethoven-Hauses, war bei Radio Taiwan International im Interview. Erfahren Sie mehr über ihn, über das Konzert und über Alois Osterwalder unter diesen Links:

Hören Sie hier das Interview mit Chang Yu-An: https://de.rti.org.tw/radio/programMessagePlayer/programId/332/id/106045

Lesen Sie hier über Herrn Chang und das Konzert: https://de.rti.org.tw/radio/programMessageView/programId/332/id/106045

Am 6. September 2022 fand in Taipei, Taiwan die Pressekonferenz anlässlich des Gedenkkonzerts KLÄNGE AUS OSTASIEN am 2. Oktober im Beethoven-Haus statt.

Finanziert wird das Konzert vom Kulturministerium der Republik China (Taiwan).

Weitere Informationen zum Konzert und zum Programm finden Sie unter: https://events.ostasien-institut.com/

Klänge aus Ostasien

Zeitgenössische Musik aus Taiwans Traditionen

Konzert zum Gedenken an Alois Osterwalder, den Gründer des Ostasien-Instituts e.V. und Brückenbauer zwischen Ost und West

Zeit: Sonntag, 02. Oktober 2022, 19:00 Uhr

Ort: Kammermusiksaal, Beethovenhaus, Bonn

Zum UNESCO World Day for Audiovisual Heritage 2021 präsentiert das Digital Archive Center for Music der National Taiwan Normal University die virtuelle Ausstellung

Taiwanese Precious Music Recording Online Exhibition – Beautiful Sound Made by Fellow Hakka

國立臺灣師範大學・音樂數位典藏中心

響應聯合國教科文組織2021「世界影音遺產日」

Dort hören Sie seltene Originalaufnahmen der Musik der Volksgruppe Hakka (Kejia 客家) und können sich mit Bild und Text (in chinesischer oder englischer Sprache) informieren – und das ganz gemütlich von zuhause aus.

Die frühesten Aufnahmen der Ausstellung entstammen der japanischen Kolonialzeit und gehen bis in die 1910er Jahre zurück. Im weiteren Verlauf geht es dann chronologisch weiter. Der zweite Abschnitt widmet sich Tonaufnahmen der 1960er Jahre, die im Rahmen des Folk Song Collection Movements insbesondere von Shi Weiliang 史惟亮 (1925-1976) gesammelt wurden. Den Höhepunkt bilden aktuelle Kompositionen, die Hakka-Elemente sozusagen ins neue Jahrtausend bringen. Zum Abschluss präsentiert die Ausstellung historische Informationen, Quellenangaben und wichtige Kontaktstellen für all diejenigen, die sich für Musik interessieren.

Die Ausstellung ist Alois Osterwalder (1933-2021) gewidmet, der nicht nur durch das jahrzehntelange Bewahren der Tonbandaufnahmen aus den 1960er Jahren, sondern auch seinen unermüdlichen Einsatz im Austausch zwischen Deutschland und Taiwan bzw. Europa und Ostasien diese Ausstellung überhaupt erst möglich gemacht hat.

Das Video zeigt die von September bis Dezember 2020 in Taiwan laufende Ausstellung des Taiwan Music Institute mit den vom OAI über Jahrzehnte bewahrten Artefaken.

Ostasien-Institut e.V. in Bonn, Germany, has preserved Taiwanese music recordings, sheet music, opera costumes and more in for decades. In 2018 it has gifted them to the Taiwan Music Institute in Taipei, where the material was professionaly restored and is now exhibited until December, 2020.

Unter dem Titel „Echoes from Afar“ 「世界影音遺產日」 wurde im September die Ausstellung der vom OAI geschenkten Musik-Artefakte vom Taiwan Music Institute 臺灣音樂館 eröffnet. Das Kultusministerium berichtet: https://www.moc.gov.tw/information_250_118735.html

Das OAI beteiligt sich mit einem Vortrag von Prof. Gerline Gild am Projekt „Beethovens Musikkulturen“ der Stadt Bonn im Rahmen des Beethoven-Jubiläums BTVN2020. Wegen der Coronavirus-Pandemie wurde das Event auf Juni 2021 verschoben.